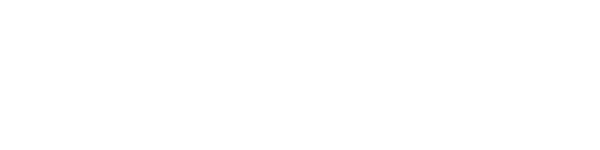

Title – All The Light We Cannot See

Author – Anthony Doerr

Type – Fiction / WW2

Reading Prompt – #6 – A book written in the present tense

I usually refrain from reading books which have more than 400 pages. But one look at the summary, and I made up my mind instantly. I’m a sucker for novels with WW2 as the background.

All The Light We Cannot See traces the lives of Marie-Laure LeBlanc, a visually impaired French girl, and Werner Pfennig, a German boy from the military. The book is non-chronological, oscillating between the present (1944) and the past, delving into the childhood of the two protagonists. Initially, it looked like Anthony Doerr was just chronicling the events of Marie-Laure & Werner in alternate chapters. But in the end, the twain did meet, much to my relief.

The story is written in the present tense, involving the readers in the action around the characters. The chapters are short, each being less than three pages. It’s a breezy read as far as the language is concerned. But as with WW2 stories, it brings to the forefront the horrors of the war.

I was engrossed in the journey of the two teenagers as they navigated through their lives. Marie-Laure comes across as a strong-willed girl, while Werner allows the goodness in him to be obscured by being a passive spectator to the atrocities committed by his mates. I still can’t fathom how people lived in constant fear, dashing to the cellars as soon as the air strikes began. My heart wept for the lost childhood of many innocent boys as they got sucked into the divisive politics of the Führer.

Some lines will remain with me.

The war drops its question mark. [The impending war is no more a rumour, it’s a reality – What a poignant way of putting it.]

Volkheimer has also discovered a bucket of paintbrushes in a corner with some watery sludge in the bottom, but how desperate will they have to become to drink that? [The war spares none, not even those on its side. It reinforces the fact that soldiers are also puppets.]

The author satiates the curiosity of the readers by detailing the aftermath of the Nazi era and how different characters emerged from it, either unscathed or scarred.

The story of Marie-Laure & Werner didn’t culminate in a romance. It reminded me of the doomed tale of Shosanna Dreyfuss and Frederick Zoller from The Inglourious Basterds. I liked how the author gave Werner feet of clay, doing nothing, while his best friend Frederick was tortured by his friends from the Hitler Youth. In an era where propaganda ruled, it would have been impossible for a young orphan to revolt against the system.

The book satisfied the reader in me. I’ll gladly overlook its length. Amidst the gloom and the horrors the war brought with it, it offered a flicker of hope and redemption.